This blog is based on an article in the Journal of Social Policy. Click here to access the article.

The mass and prolonged unemployment resulting from the Great Recession challenged the Unemployment Insurance (UI) systems in many countries. In the wake of the Great Recession, EU member states have debated over the establishment of a supranational EU unemployment benefits scheme (EUBS) to stabilise the economy and support jobless workers in Europe. Increasing attention has been paid to the institutional designs of the American federal-state UI system and the policy implications for a EUBS. This paper investigates the subnational variation in UI policy designs and their underlying policy logic in the United States. It highlights the unequal and weakening social protection under the American federal-state UI system.

What are the features of the American UI system?

The American UI began as a New Deal effort in response to the Great Depression in the 1930s. It provides unemployment compensation to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The American UI system is financed by both federal and state taxes on employers. The federal government and states share the responsibilities of the programme design, including dimensions of financing, eligibility, and benefit rules. Each programme dimension has the potential to enhance social protection in respect to financing sufficiency, programme accessibility, and benefit adequacy. There have been considerable variations in the taxable wage bases, tax rates, qualifying wages, allowable reasons for leaving a job, benefit level, and benefit duration across state.

What are the distinct state UI approaches and their underlying policy logic?

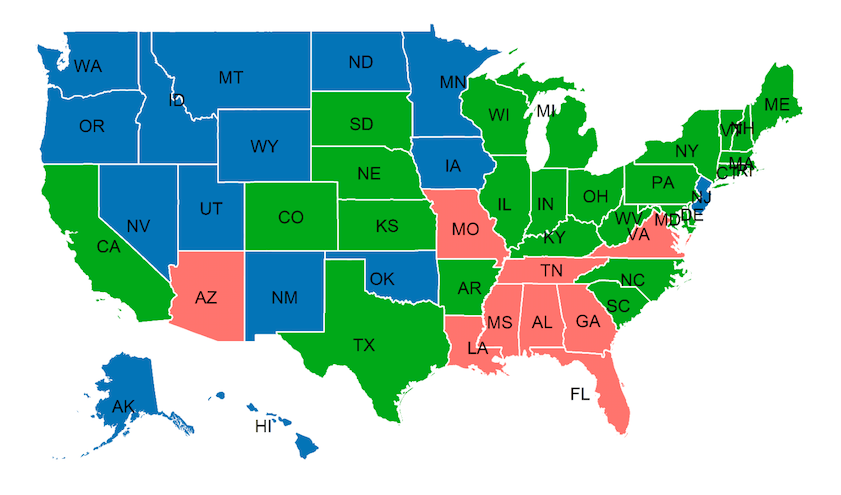

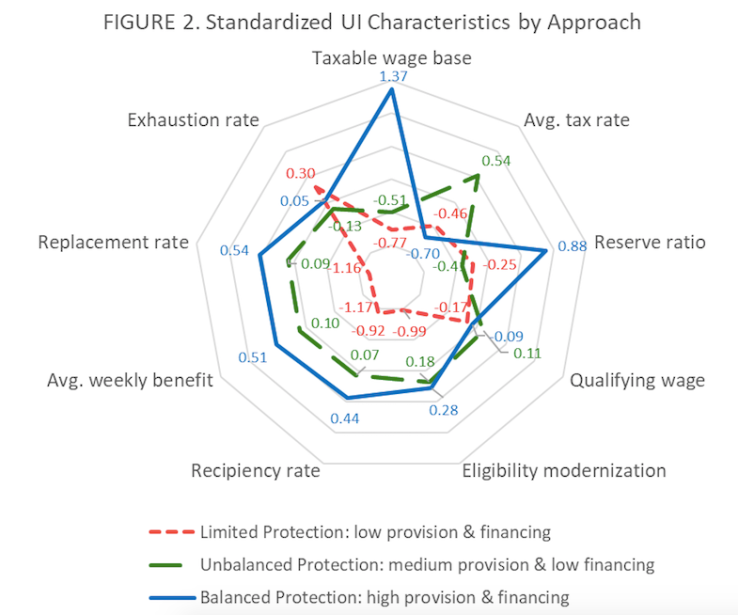

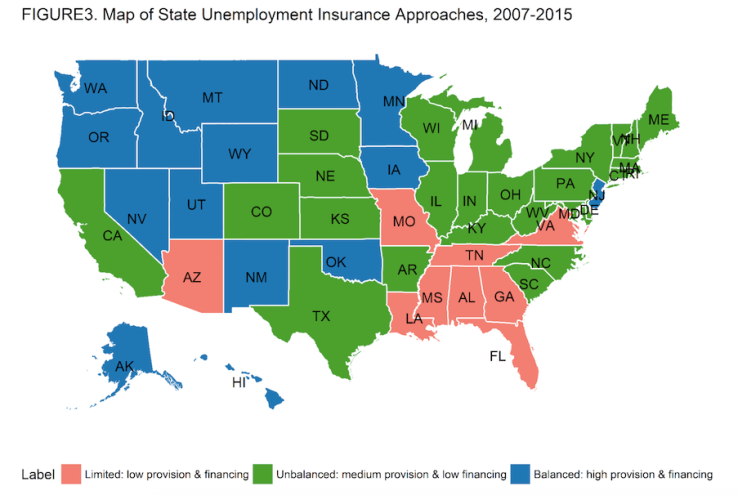

In this paper, I define UI approaches as ways to design and implement UI that have interrelated elements working as unified systems to achieve social protection. Different UI approaches reflect mixtures of four policy logics: social protection, economic stabilisation, work disincentives, and interstate competition and political-economic contexts. I conducted a model-based cluster analysis to examine multiple policy indicators of 51 states’ UI programmes during and after the Great Recession (2007-2015) and identified three distinct UI approaches (see Figure 2). After assigning the cluster membership to each state (see Figure 3), I performed fixed-effect panel regression models to test the policy logic underlying the policy responses of three different UI approaches, respectively.

First, the limited social protection approach features low benefit generosity with a weak financing capacity. For every 100 unemployed workers, only 16 received UI benefits in 2015. On average, the weekly benefit was $251 and the maximum duration of benefit was 23 weeks. The average reserve ratio (trust fund balance as a per cent of the total payroll) was 0.72 in 2015 compared to 1.14 in 2007, just prior to the Great Recession. The policy choices made by these states reflected a low commitment to social protection and weak countercyclical responses to the macroeconomic conditions in an increasingly conservative political setting. These states required more job search activities per week than their counterparts to avoid a work disincentive of benefit receipt; they also tended to reduce their benefit levels to maintain their economic competitive advantages relative to their neighbouring states.

Second, the unbalanced social protection approach features moderate benefit generosity with low financing sufficiency. In an average state, approximately 29 out of every 100 unemployed workers received UI benefits in 2015. The average weekly benefit was $321 and the average maximum duration of benefit available for workers was 25 weeks in 2015. The average reserve ratio was always below 1 per cent during the 2007-2015 period, with an overall decrease of 0.24. These states made uncoordinated policy choices which undermined a higher level of social protection. For example, many states expanded their eligibility rules to benefit more disadvantaged workers during the Great Recession. However, some of them reduced the benefit levels and duration in the context of a prolonged economic recession and an increasingly conservative political environment.

Third, the balanced social protection approach features the most inclusive and generous provision with a strong financing structure. In 2015 approximately 35 per cent of unemployed workers received UI benefits in a typical state. On average, the weekly benefit was $363, the maximum duration of benefit was 26 weeks, and the reserve ratio was 2 per cent in 2015. UI systems in these states played a crucial role in smoothing macroeconomic fluctuations. These states tended to improve or maintain a reasonable level of social protection during and after the Great Recession. However, only 15 out of 51 states take the balanced social protection approach.

The majority of American workers are living in states without a robust UI system that provides strong unemployment protection. The nationwide declining trend in social protection in the post-recessionary period shows that the American federal-state UI system is unprepared for the next economic recession. I argue that a stronger role of the federal government in setting the minimum standards of social protection is crucial to ensure the economic security for unemployed workers and their families (e.g, a uniform maximum duration of unemployment benefit of 26 weeks and a minimum benefit replacement rate of 40%).

Drawing on the US experience, a supranational EUBS design needs to consider reasonable basic social protection for European workers and harmonise different national unemployment benefit schemes. Future research could use the conceptual framework established in this paper and the cluster analysis of the unemployment benefit schemes across EU member states to inform EUBS debates and policy designs.

About the author

Yu-Ling Chang is Assistant Professor at the School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Chang’s scholarship focuses on poverty, income inequality, and the social safety net policy. Her research addresses both the process of policymaking and the consequences of public policies for economically disadvantages populations.